Friday, March 4, 2011

Recently, Christine Fahlund, the financial planning director at mutual fund company T. Rowe Price circulated what you'd have to call a pretty novel retirement planning strategy for boomers. Stop saving. Instead, spend the money on cruises and other indulgences until you retire. Do this, her calculations showed, and you'll end up with 70 percent more income in retirement than someone who saves like crazy for the rest of his or her career.

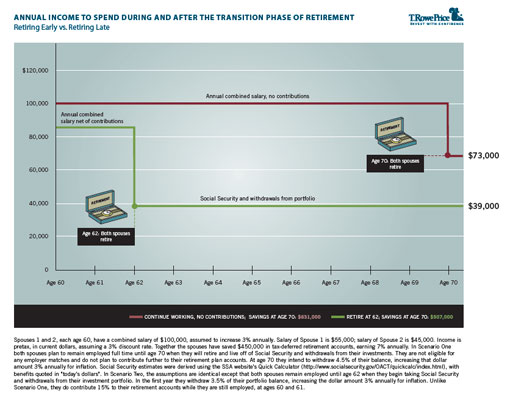

Why, yes, there IS a catch: You have to work until age 70. Fahlund contrasts the results of that tactic with those of a hard-saving boomer couple who leave the workforce as soon as they become eligible for Social Security at age 62. You can see how it works out in the chart below. Maybe it's cheating to compare retiring at 62 to slaving away until 70, but Fahlund's point is, it all depends on how you define slaving.I give her credit. Fahlund's approach addresses one of the key dilemmas anyone faces in planning for financial independence. You fix a lot of retirement financing issues if you stay with your job until 70. CBS MoneyWatch writers like Charlie Farrell, Carla Fried and Steve Vernon have written extensively about the powerful financial upside of working longer. Among other things:

• Retiring at 70 rather than 62 means you have to support yourself without a paycheck for eight fewer years. That means that, for same size nest egg, you get more income.

•Your Social Security benefit grows every year you delaying claiming. For a top earner, the maximum Social Security benefit grows from $21,600 a year for someone retiring at 62 to $38,300 at 70. Claiming that fatter age-70 benefit means you have to provide less of your retirement income out of your own savings.

•You have eight more years to save and your savings have eight more years to grow.

Only problem is, who wants to work until 70? It sounds like the definition of retirement planning failure, not success. Fahlund's strategy finesses the problem by, essentially, inviting you to start enjoying "retirement" before you leave work. You trade the dream of leaving work in your early 60s for the extra cash flow of staying on the job. To make the eight extra years of servitude palatable, you spend the money you had been saving for retirement.

Okay: You get the concept of living it up in your 60s. But how does not saving leave you with more income than saving? A lot of is due to the aforementioned benefits of delayed retirement: The age-70 retirees have to stretch their nest egg over eight fewer years of life, and they collect a bigger Social Security benefit. But a lot of it also comes from earnings on savings they already had. Fahlund's illustration assumes both couples hit age 60 with $450,000 in the pot. Yes, the hard-saving couple hit age 62 with more in the bank. But then they have to start drawing on their savings to cover living expenses. Meanwhile, the stay-at-work couple are able to their nest egg grow another eight years (in Fahlund's example at 7% annually). By the time they hit 70, they have much more in their nest egg than the early retirees, even though they didn't save a penny of their salaries for the past decade.

Can you do this? Yes. Will it work out for you the way it does in Fahlund's illustration? Don't count on it. The model is highly dependent on the return over those years you continue working but not saving. What if, instead of getting 7% you get 2.8%, the rate of return on 7-year Treasury bonds now?

More important, what if you start spending your savings on cruises and spa vacations at 62, as the delayed retirees do in Fahlund's illustration, and the boss cans you at 64? Some 40% of retirees never make it to their intended retirement age because of illness or layoff — and their intended retirement age is usually 65, let alone 70.

You can't control the return on your retirement stash, and you can't necessarily control when you get to call it quits. Fahlund's strategy is psychologically astute, in that it blends the security of working longer with the pleasures of enjoying life while you're still young enough to enjoy it. But in the end, Fahlund's plan depends on two things that are outside your control: Market returns and the length of your career. To stop saving in the hope that you won't need to draw on your nest egg until you're in your eighth decade is a gamble.What's the takeaway? There's no way around the fact that the best retirement strategy is a balance between three sound but contradictory pieces of advice. Work as long as you can. Save like you'll be on your own tomorrow. Live each day like it could be your last.

No comments:

Post a Comment